January 2023

The Adjudication Society & King’s College London Report on Adjudication: Thoughts for the future?

On 3 November 2022, the Adjudication Society & King’s College London Report on Adjudication was launched at the Adjudication Society’s Annual Conference in Edinburgh (the “Report”). Written by Professor Nazzini and Aleksander Kalisz, the Report provides some of the most comprehensive statistics available on the practise of Adjudication in the United Kingdom.1 Claire King, the author, had the pleasure of sitting on the Project Steering Committee for the Report.2

In this Insight, we review what the author considers to be the most interesting findings within the Report and asks what they suggest for the future of adjudication generally.3

Overview and general impressions of the process

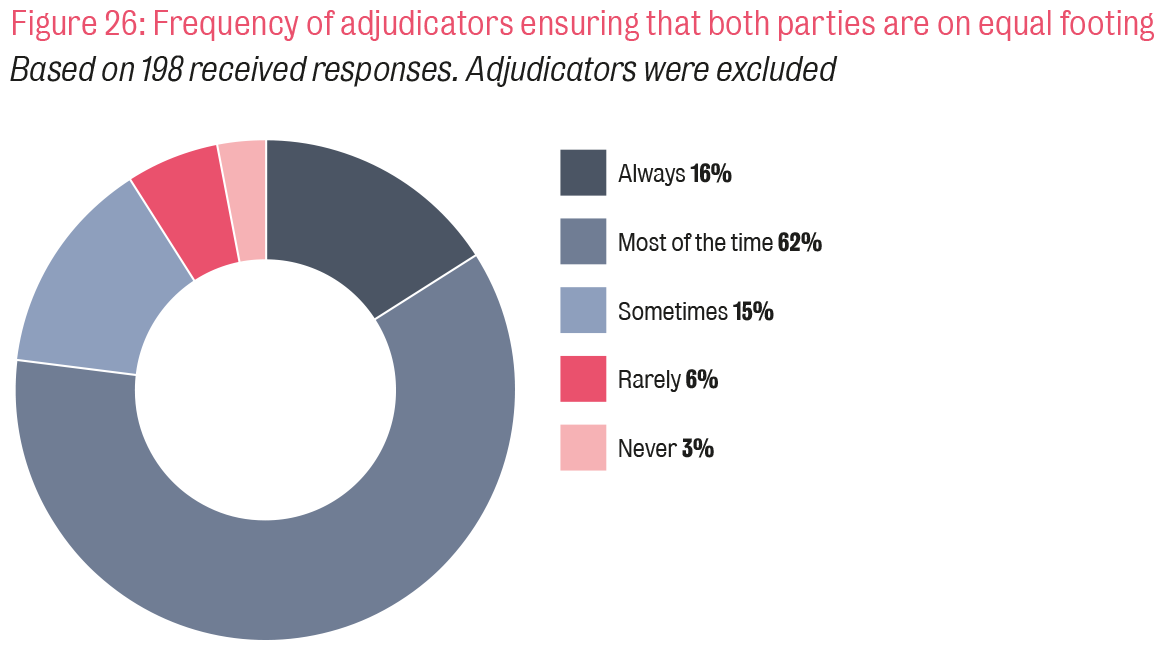

As noted by Lord Justice Coulson in his Foreword to the Report, “It reveals many attitudes and statistics that support the generally positive view [of Adjudication] to which I have referred.” Overall, adjudication comes out of the Report relatively well. For example, there is a general perception of procedural fairness in adjudication. 78% of respondents agreed that adjudicators ensure that the parties are on an equal footing always or most of the time. Only 7% of respondents thought that they do so rarely or never. That is plainly a vote of confidence in the process overall.

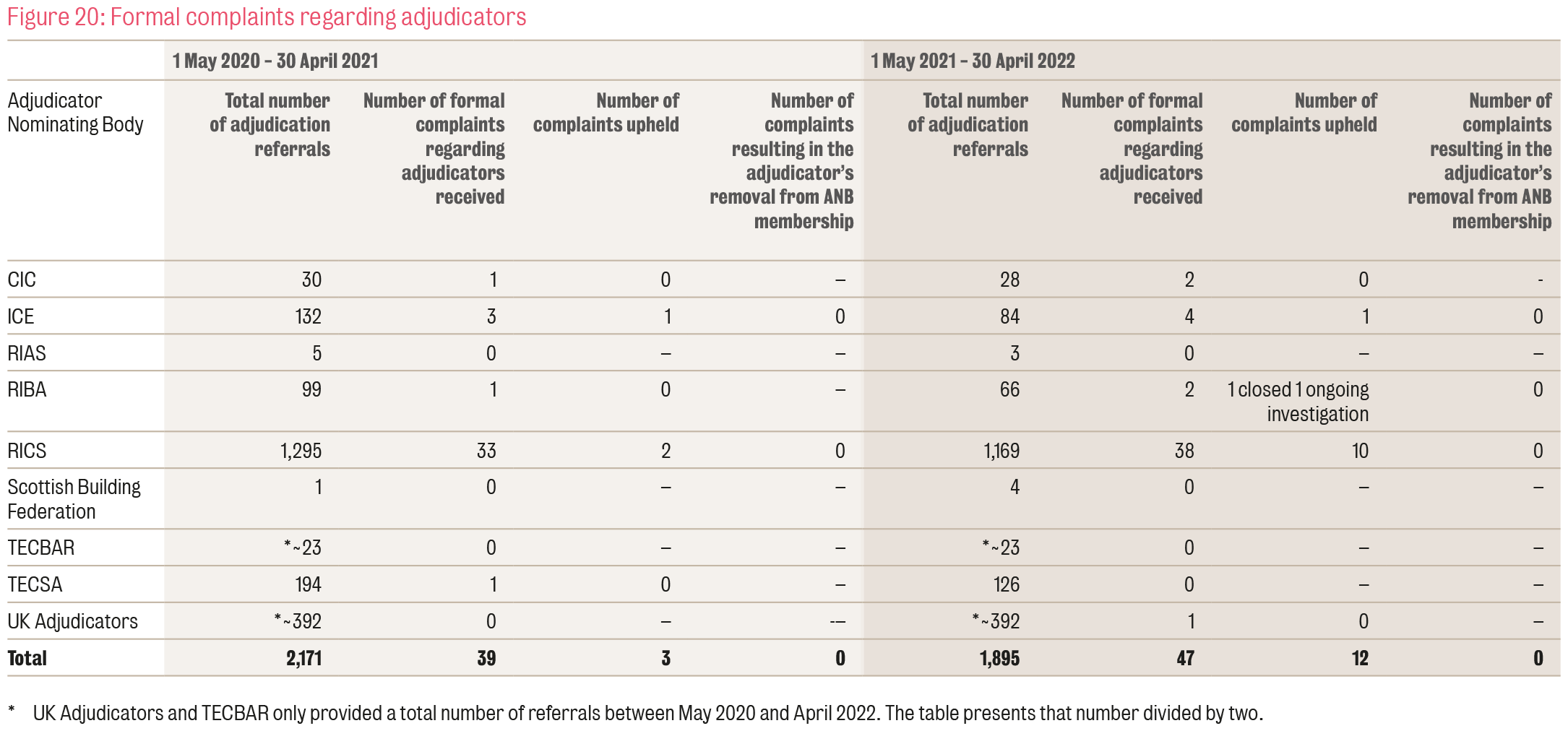

There were also low numbers of complaints about adjudicators to the Adjudicator Nominating Bodies (“ANBs”). As recorded in the Report, RICS has the most referrals and (presumably, therefore) the most complaints at 2.5% and 3.2% of total referrals for the year 1 May 2020 to 30 April 2021, and 1 May 2021 to 30 April 2022 respectively. No adjudicators were removed from panels and it is noticeable that some smaller ANBs had no complaints at all.

However, this lack of complaints doesn’t sit well with the statistics in relation to the suspected bias of adjudicators, themselves subject to some debate, as to which, see further below.

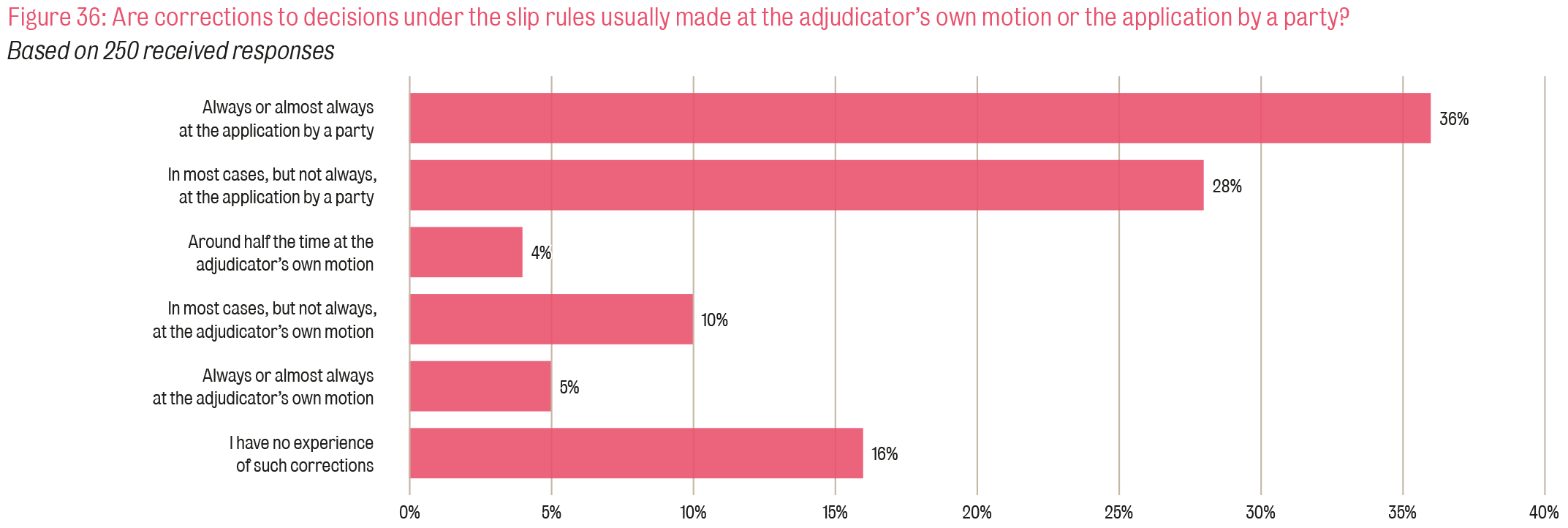

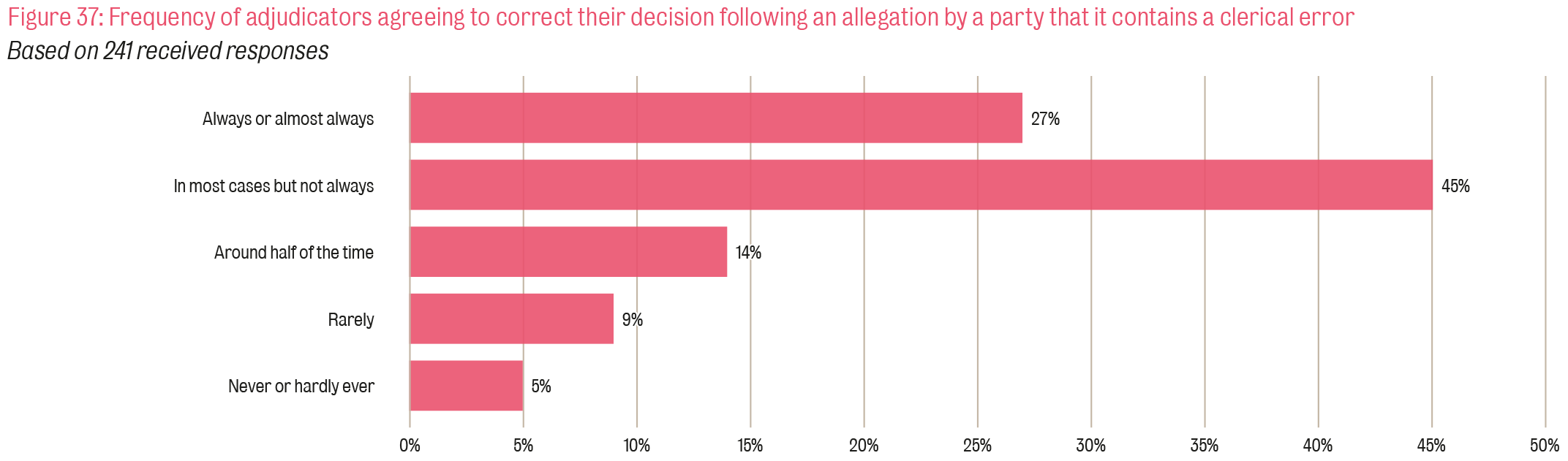

The slip rule also seems to be working relatively smoothly. Generally, “slips” are picked up by the parties rather than the adjudicator, which is perhaps unsurprising:

They are then corrected by the adjudicator once raised (as to which, see below).

Finally, the statistics in relation to judgments published by the TCC (High Court) since 2011 demonstrate that the Courts have generally taken a robust approach towards enforcement. The vast majority of decisions are enforced. That said, summary enforcement was declined in 21% of cases handled by the TCC (High Court). As summarised in the Report: “Jurisdictional objections defeated 9.5% of enforcement applications, whilst natural justice defeated 4.8%. In a further 2.1% of cases, a combination of both jurisdiction and natural justice allegations defeated enforcement.”4 Other grounds included insolvency (4.8% of cases).

Apparent Bias of Adjudicators

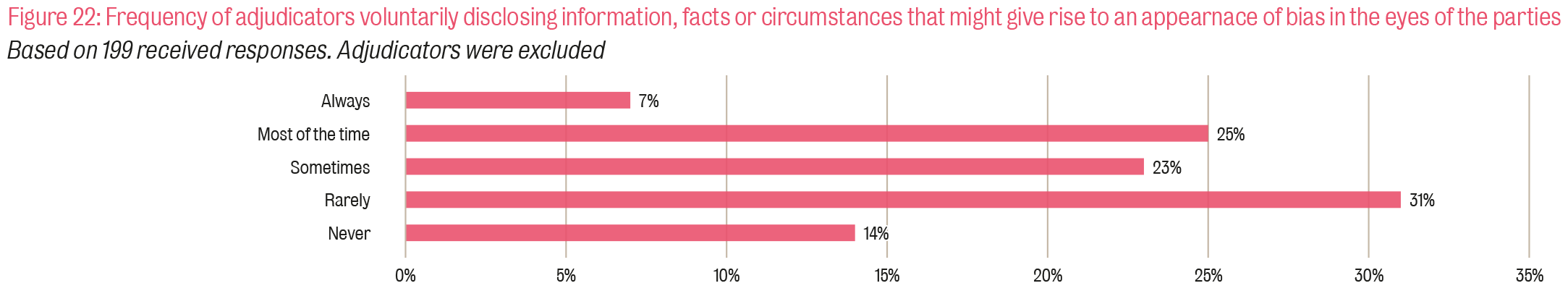

One of the most headline-grabbing findings (and one that is picked up on by Lord Justice Coulson in his Foreword to the Report) relates to apparent bias of adjudicators. The Report itself found that adjudicators very rarely voluntarily disclose any information, facts or circumstances that might give rise to the appearance of bias in the eyes of the parties. This is shown in the figure below.

The question then becomes one of whether this is simply because it rarely, if ever, occurs that an adjudicator has anything at all to disclose. The answer to that, unfortunately, appears to be no.

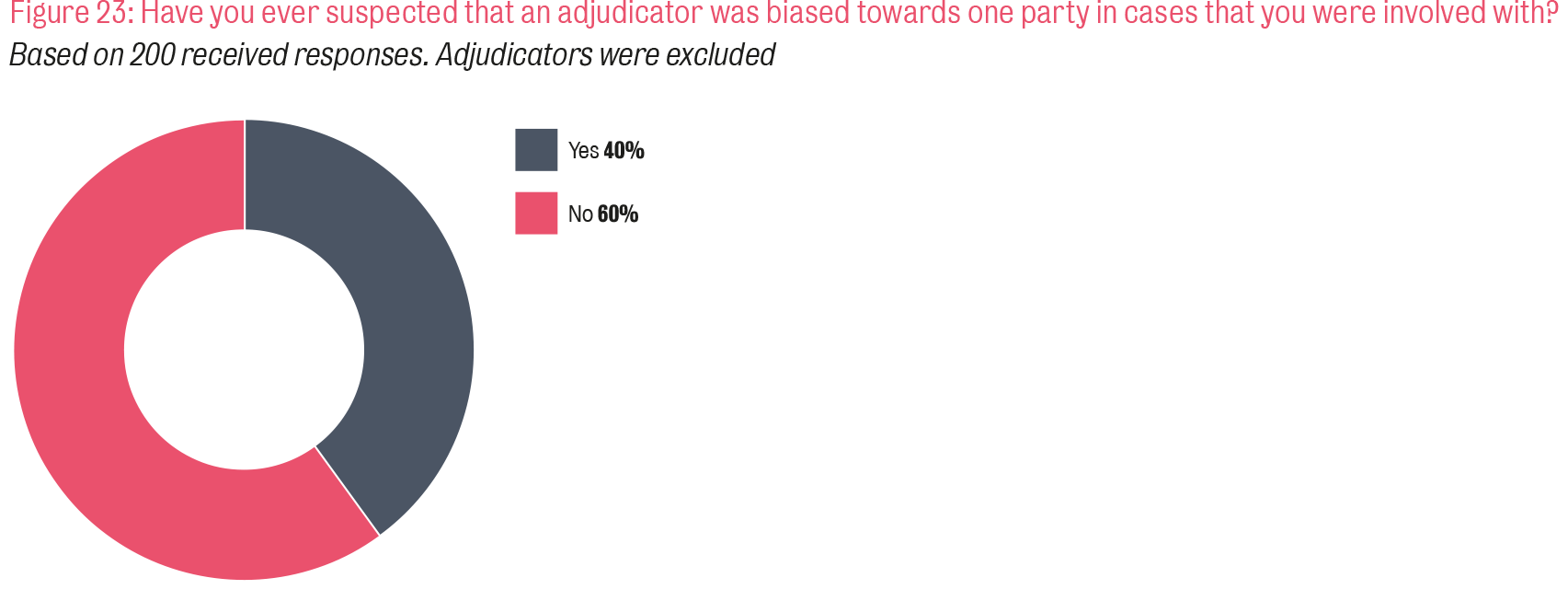

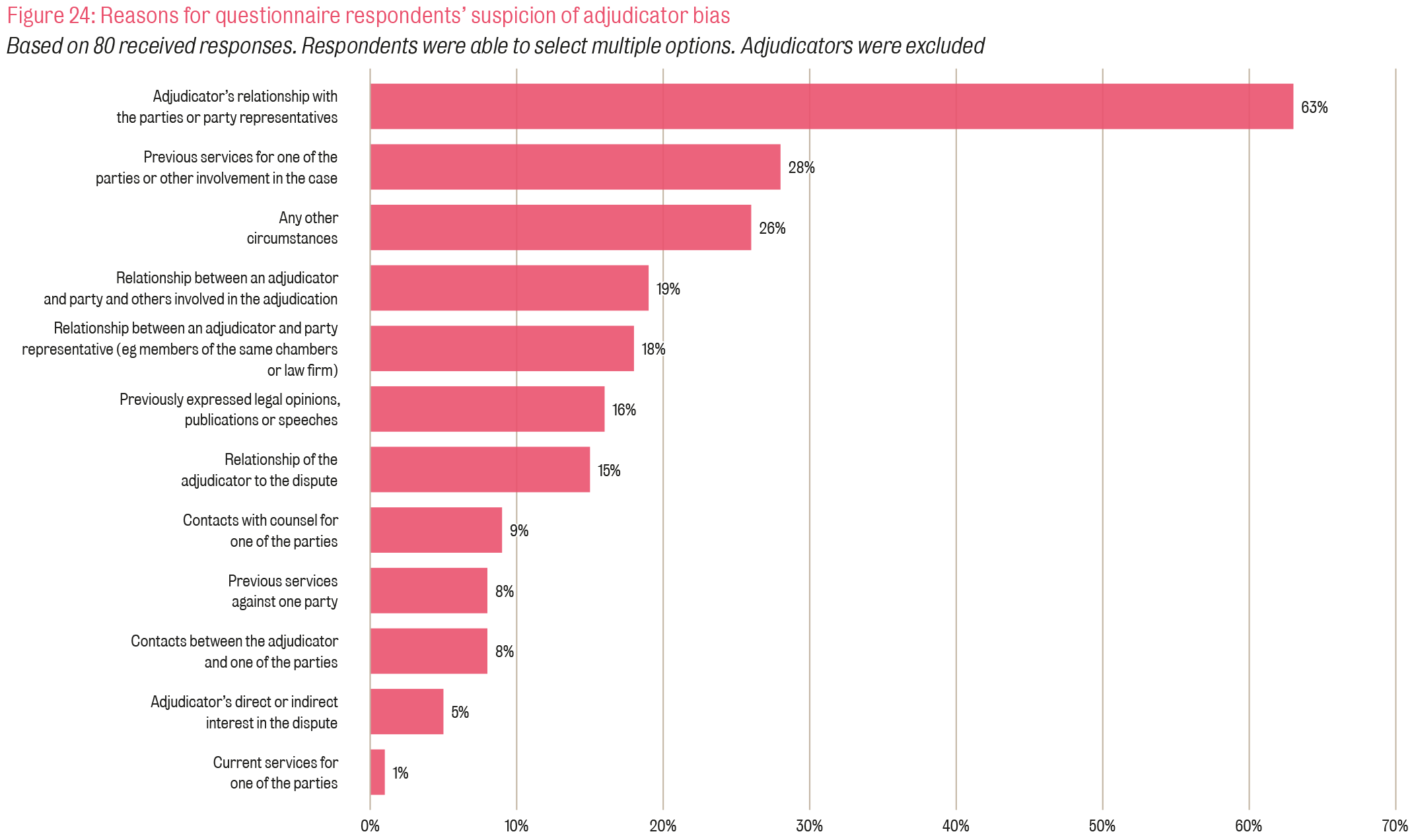

As can be seen from the graphic above, 40% of parties have suspected that adjudicators were biased in a case they were involved with. The reasons for this were varied but include (suspected) relationships with other parties:

As Lord Justice Coulson states, this:

“suggests a potential problem with construction adjudication which has been lurking close to the surface for quite a while now. Section 11, and figures 23 and 24, pull no punches on the issue of perceived bias ... That is a truly startling message, and it is to be hoped that the comprehensive and authoritative nature of this Report will mean that it is promptly and fully addressed.” [Emphasis added]

It has been pointed out by commentators that the questions posed in relation to bias suspicions asks if the respondent has ever had any suspicions in their entire experience of adjudication, and that could mean over a very long time period. Accordingly, next year, it has been suggested that the question only asks about suspicions of bias over the last year and that this will illustrate that this is a misrepresentation of the issue.

However, based on experience, there is sometimes a suspicion that, perhaps, an adjudicator has worked with parties before or is familiar with them and this can give rise to a feeling of unfairness even if unjustified. There is also the tricky question of at what point does the repeated appointment of one adjudicator by a party need to be disclosed? In the case of Cofely Limited v Anthony Bingham and Knowles Limited [2016] EWHC 240, the fact that 25% of that particular arbitrator (and also adjudicator) fee income over three years came from 25 appointments involving Knowles was deemed sufficient to constitute apparent bias. That is obviously an extreme case. However, at the moment, there is no universal code of ethics requiring adjudicators to reveal what percentage (or what value) of appointments have come to them from particular parties or particular representatives or the thresholds at which disclosures should be made.

The Report’s suggestion that a code applying to all of the ANBs setting out when disclosures should be made by adjudicators along the lines of the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interests in Arbitration5 is, in the author’s view, a sensible one. At the very least, if such a code applies, and the adjudicator confirms they are abiding by it, it will give parties more confidence in the process and that no such bias exists. Avoiding a slight feeling of discomfort due to an adjudicator’s familiarity with the other side is important. It may be that there is no actual bias arising out of that or as a result of it – and certainly nothing specific enough to allow a complaint to be made to the ANB – but the need to ensure there is always confidence in the process should not be ignored.

Publication of decisions?

The Report also examines whether there would be any merit in publishing the decisions of adjudicators either in full or on a redacted basis. A clear argument for publishing decisions is to drive up quality. Quality and sensible decision making can sometimes be an issue but it does not give rise to any right to challenge the decision itself. There is also sometimes a reluctance to complain to an ANB about the quality of a decision as there is always a risk that the same adjudicator will be appointed again in the future and may (theoretically) hold a grudge.

Other jurisdictions do publish decisions. The Singaporean model allows them to be published but with redactions, whilst in Queensland, Australia, they are published fully.

Interestingly, support for publishing the decision on a redacted basis was fairly high – 30% of respondents favoured the idea. Only 8% favoured publication without redactions. That said, the majority did not favour publication (58%) and perhaps this is understandable as, unless the matter goes to enforcement, decisions can be kept relatively confidential to the parties.

Another potential way to drive up quality would be for ANBs to actively ask for feedback on adjudicators at the end of the process. Certain ANBs ask adjudicators for feedback at the end of the process but some feedback from the parties (anonymised) may also be sensible? The Courts are, after all, not looking for the quality of decision making.

Abuse of process?

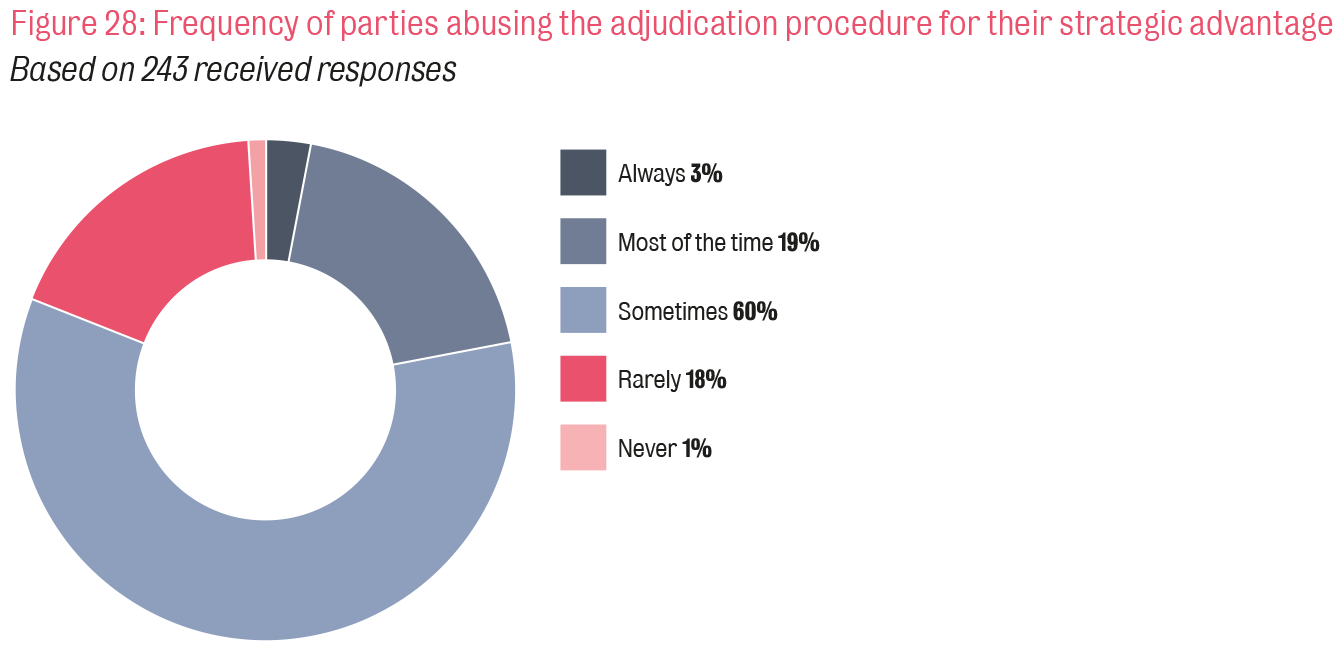

The Report does suggest that the adjudication process can sometimes be perceived as open to abuse. 22% of respondents answered that parties abusing the adjudication process for their strategic advantage occurs always or most of the time. 59% stated that parties abuse the adjudication procedure sometimes. Only 1% stated that such abuse never takes place. Figure 28 provides a visual summary of the responses.

The sorts of abuse suggested by the Report include that the referring party generally has significantly longer to prepare their case than the respondent as well as the notorious “smash and grab” process which can result in very significant implications for the respondent’s cashflow if the process is successful. Having just survived another Christmas with the threat of last minute adjudications when those charged with responding are not necessarily available, this form of “abuse” could also potentially be added to the list.

The Report suggests ways in which adjudicators can mitigate these issues whilst noting that “smash and grabs” themselves can only be stopped if there is a reform of the Act (which would arguably conflict with the Act’s goal of encouraging cashflow). However, the Report does not explore in detail the types of abuse that the respondents are particularly concerned with, and this may be something for follow up in subsequent reports.

Should the statutory exceptions to adjudication be modified?

In the last chapter of the Report, it discusses whether some of the statutory exceptions contained within Sections 105 (2) (excluding a large number of energy related contracts) and 106 (the Residential Occupiers Exception) of the Act should be removed. A fair number of respondents suggested that the energy exception, in particular, was out of date particularly given difficulties caused when some contracts on a site fell under the Act and others did not. There were also suggestions that the Residential Occupier’s Exception should be removed.6

This is certainly an area that would need to be explored further in subsequent reports (and, indeed, by BEIS should the reform of the Act come back onto the political agenda). Whilst this author can see the logic of removing the energy exceptions, the removal of the Residential Occupier’s Exception could place homeowners in a very difficult position, especially if they were subject to a smash and grab. The implications of a homeowner having to shoulder the burden of the costs of adjudication, even if they win, as well as dealing with the short timescales, would also need very careful thought indeed.

Diversity in Adjudication

Finally, one of the most commented on statistics cited from the Report, is that only 7.88% of adjudicators on the ANBs who publish their lists online are women. No statistics at all are available on any other protected characteristics as defined by the English Equality Act 2010. Indeed, little seems to have changed since I wrote a blog on this topic in August 2020, which also highlighted the dearth of female adjudicators and the lack of progress when compared to arbitration which has improved matters significantly over the last 5 years.7

The 7.88% statistic was the subject of much debate at the Adjudication Society Annual Conference (as well as the King’s College Construction Centre’s 35th Anniversary Conference) with some suggesting outright that there were simply no females available to fulfil the role in certain fields (such as from an engineering background). The lack of qualified female engineers was suggested as one reason why there are no female adjudicators on the ICE Panel. Similar comments were apparently made in the past in relation to arbitration. Indeed, GAR has recently compiled a list of female arbitrators called a “Compendium of Unicorns” noting that the inclusion of “’Unicorns’ in the title reflects a comment, once upon a time, by a particular man that he would appoint qualified female arbitrators, if only he could find some.”8 Whilst it may be harder to recruit adjudicators from some disciplines (such as engineering), the assertion that there is a total lack of any qualified candidates seems hard to fathom especially as there was a practising female engineer adjudicator delivering the diversity workshop at the Adjudication Society Conference where the comments were made.

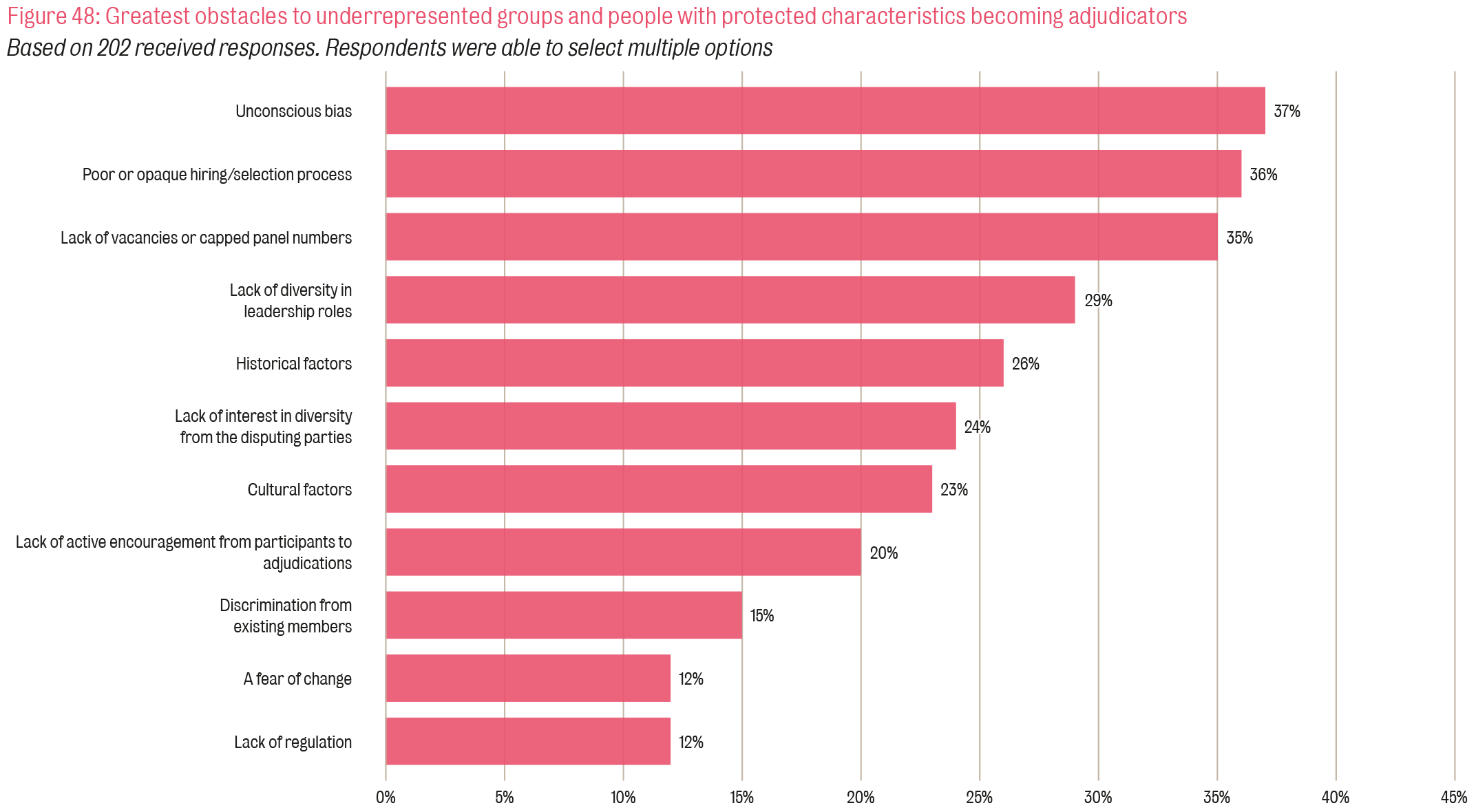

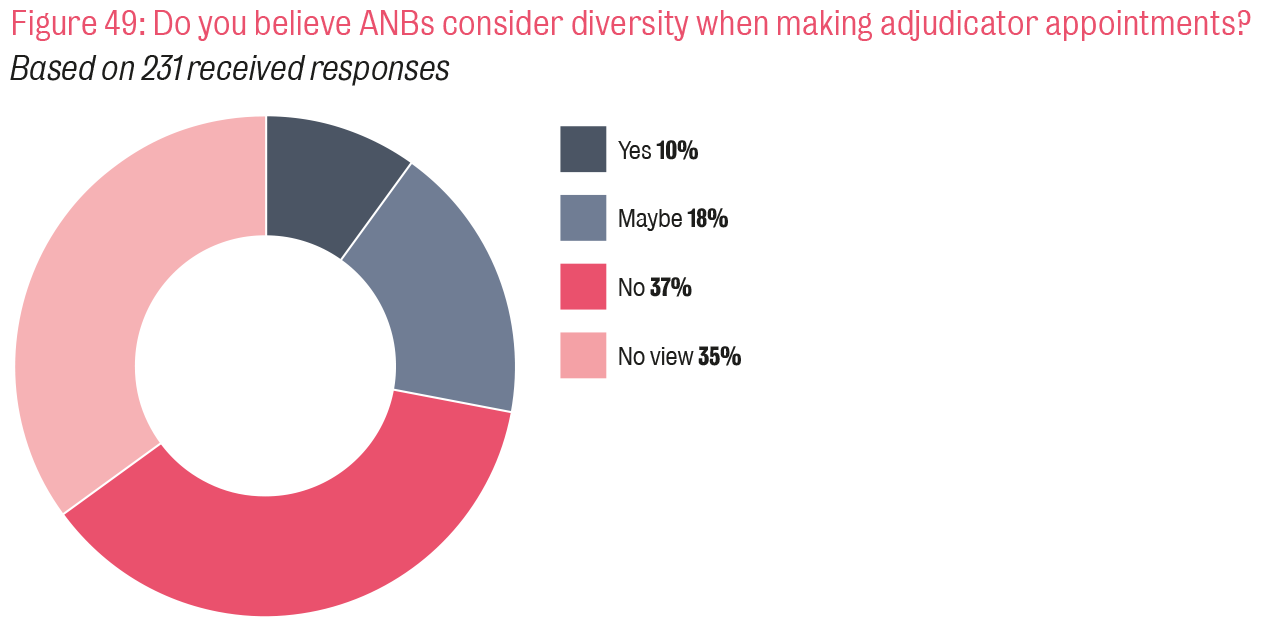

The Report itself suggests that unconscious bias, poor and/or opaque selection processes and the lack of space on ANBs are the major barriers to greater diversity (for the others identified, see below).

Interestingly, respondents in the Report don’t appear to view the diversity of adjudicators as a major priority and neither (prior to the Report being published at least) do the ANBs.

Perhaps these rather depressing statistics also underline that established interests rarely vote for change unless pushed to do so?

In any event, the statistic in the Report does appear to have shone the light on the lack of diversity generally in adjudication and the need to open up panels to new talent (not just female, but more generally, including younger adjudicators). This shouldn’t, in my view, be regarded as a dilution of quality, which again, is too often used as an (un-evidenced) excuse to keep the panels relatively closed to newcomers. Increasing, the panel’s diversity is instead a chance to improve the quality of decision making in adjudication and increase confidence in the system generally. If women aren’t coming forward to sit on those panels, then more needs to be done to persuade the talent that is out there to come forward.9

It is clear in any event that pressure needs to be applied on the ANBs to bring about change in the same way that it was in relation to arbitration via the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge10 and organisations such as ArbitralWomen.11 The Adjudication Society will be announcing steps to apply such pressure shortly.

Conclusions

Whilst the Report paints a generally positive picture of adjudication, it also highlights that there is room for improvement in the system as it stands. In particular, the production of clear, universal guidelines on when disclosures should be made to prevent the suspicion of bias should be carefully considered. It is also clear that more needs to be done to ensure that the diversity of adjudicators is improved as it has in arbitration (rather dramatically) in recent years.

Finally, I should emphasise that the views expressed in this Insight are personal to the author and that reading this article is, of course, no substitute for reading the full Report which can be downloaded from the Adjudication Society’s website.12

- 1. The Report builds on the previous research by J L Milligan sponsored by the Adjudication Society.

- 2. Others on the Project Steering Committee included: Jonathan Cope, Adjudicator and Arbitrator at MCMS; Kathy Gal, Director and Architect at gal.com; Hamish Lal, Partner at Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld; Lynne McCafferty KC, Barrister at 4 Pump Court and James Pickavance, Partner at Jones Day.

- 3. By Claire King. With thanks and acknowledgement to the authors and King’s College, London for the use of the graphics contained within this article.

- 4. See summary on page 82 of the Report.

- 5. See the IBA Guidelines on Conflict of Interest [1]

- 6. See page 75 of the Report.

- 7. See Lessons in gender diversity: What can Adjudicator Nominating Bodies learn from arbitration?

- 8. See Compendium of Unicorns: A Global Guide to Women Arbitrators [2]

- 9. Persuading female talent to put themselves forward was noted as a key step with the ICC “Report of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings” (published in 2020) (the “ICCA Report”) noting that "In recent years, there has been a concerted effort by the international arbitral community to both encourage more female arbitrators to put themselves forward in the first place and then to get them appointed."

- 10. See Equal Representation in Arbitration [3]

- 11. https://www.arbitralwomen.org/ [4]

- 12. https://www.adjudication.org/resources/research [5]